I've Only Got A Technician License!

(The technical information presented here is not new to me. I have borrowed heavily from several internet sites and paraphrased much of their content.)

I think that one of the failures of the ham community, as a whole, is the lack of information provided to newly licensed technicians about the many opportunities available to them.

Too many times a new tech is advised to find a local club and join it. Once they join, the standard jargon is, “Buy a hand held VHF, find a repeater, and get on the air with one of the local nets. This will get you over “mic fright” and acquaint you with radio procedures.” After that they are pretty much left on their own to find what opportunities are available to them. Unless they are lucky, they sit through club presentations that seem to be geared to the General or Extra class licensee without it ever being pointed out that this is an area in which they too can participate.

Let’s face it. After the initial thrill of actually contacting someone by “checking into a net”, it soon becomes boring and monotonous to check in and then spend 30 – 45 minutes listening to others do the same thing. I think this is where we lose too many techs. Their valid questions being, “Is this all there is to being a ham? If so, is it worth my time to continue?”

The most obvious answer to this question is “find something you are interested in doing and do it.” For many, this is easy, just think about what got you interested in ham radio and follow that path. Others “want to do ham radio” but may not be sure where to start. While this article will not be a “How to do it”, I hope it gives you some insight into what is available to you as a tech and some ideas on what to do.

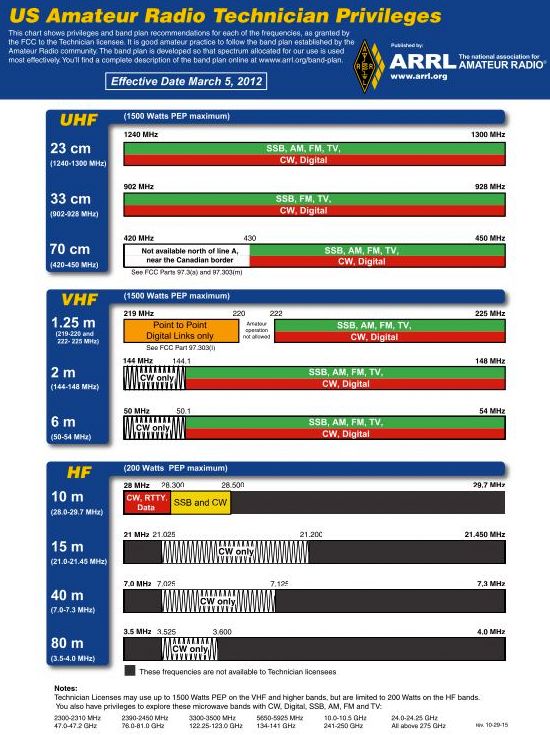

First, let’s start by looking at your privileges, also called a band plan (a larger chart can be printed out here):

The first thing to note is that you have privileges in three (3) areas: HF, VHF, & UHF. In the HF area you can access the 80m, 40m, 15m, & 10m bands. In the VHF your privileges are 6m, 2m, & 1.25m bands. And, in the UHF area you are allowed to operate in the 70cm, 33cm, & 23cm bands.

The second is that you have a max output of 200Watts PEP (Peak Envelope Power) on HF, 1200 Watts PEP on VHF, & 1500 Watts PEP on UHF. I doubt if you will ever use that much power. People talk all over the world on less than 5 Watts PEP!

The third thing to note is the squiggly lines in some bands. This indicates CW Only (Continuous Wave – AKA Morse code). So, unless you know CW, you cannot use these locations in the bands. This means the 80m, 40m, 15m bands are out unless you know CW.

As an aside: an unabashed plug for Dan Parkin – W7BID (BCARC’s CW guru). Many hams, once they learned CW, will not do anything else. (I have a cousin by marriage that got his Novice license as a teen in the late 1940’s and will not bother to upgrade to General. We don’t communicate using ham radio because I don’t know CW and he won’t do anything else.) So try CW, you might be surprised.

And, last, you will note that you can use SSB (single side band), AM, FM, TV, and CW.

Overview

SSB: Single sideband is the preferred mode for amateur radio voice communications on the HF bands and 50 MHz. It is also used, but to a much smaller extent at frequencies above this in the VHF and UHF bands.

Single sideband provides a very effective mode for amateur radio communication, and it is efficient in both its use of spectrum and power.

Single sideband has been in use in amateur radio for many years and it is available on a huge variety of amateur radio equipment. Its widespread availability is another reason for its level of usage.

AM: Amplitude Modulation (AM) offers the experimenter, homebrewer, and radio restoration buff great opportunities to learn, build, and enjoy radio. AM was once the main voice mode in amateur radio. Now it is a well regarded specialty within the hobby. The simplicity of AM circuit design encourages hands-on restoration, modification and homebrew construction to an extent no longer found among contemporary radios.

One of the attractions of using AM on HF is that the mode can offer a warm, inviting sound for the style of operating found in this part of the hobby. Operators frequently make extended transmissions while discussing a technical pursuit, or during nostalgic storytelling much in the manner of “old style” broadcast radio. Conversations take place both one-on-one and in group “roundtables,” where there is a taking-of-turns among several operators, including a more formal gathering taking place on a regular schedule.

FM: Frequency modulation provides many advantages when used for amateur radio communications.

Frequency modulation tends to be used where mobile and portable operation has been more widely used. The reason for this is its greater resilience to noise and signal strength variations when compared to AM.

In view of this, FM has gained very widespread acceptance on the VHF and UHF amateur radio bands and in addition to this it is also used on the Ten Meter ham radio band as well.

TV: Any Technician class licensed Radio Amateur can transmit live action black and white or color video along with audio in the 70cm and above bands to other hams simplex or through ATV repeaters.

Assuming you have a Tech license and some basic 2m or 70 cm radio equipment, here are some activities (in no particular order):

Public Service

There are many opportunities to get involved in helping out with events such as walkathons, marathons, bike races, etc. Communications support may be provided by a ham radio club or the local Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES) group. The Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) is another public service organization, normally associated with a governmental agency such as the county sheriff’s department. Sometimes ARES and RACES are combined into one group. The ARRL has a web page that compares the two organizations.

Most ARES and RACES groups have some kind of “registration database” for you to sign up. However, it usually works best to reach out and find the local hams that are in charge of these groups and let them know you are interested. Find out when they hold their meetings and on-the-air nets and join in. Make yourself visible and available.

Emergency Communications

Being prepared for emergencies boils down to two basic questions: 1) what are the conditions that you are preparing for? 2) Who do you want to communicate with? Most likely, you need to be ready for a power outage of some duration, which implies the use of battery backup or a gasoline generator to power your radio equipment. Who you want to communicate with varies from just your immediate family over short distances to being able to contact other hams much further away. Thinking through the answers to these two questions will get you started on creating the desired communication capability.

Find A VHF/UHF Repeater

Another way to connect with the local amateur radio community is via VHF/UHF repeaters. These things are the utility mode for communicating locally. This doesn’t have to be just “checking in” on a local net. There are many nets devoted to various interests with a lot of chats between users. Check our website’s “Net” page for a partial listing and listen in to find one that fits your interests.

Develop Your Home Station

Many hams start out with a VHF/UHF handheld transceiver (HT), which gets them on the air quickly. This really is a ham shack in your hand, which is useful for many activities. By itself, the HT (handi-talkie) has limited range; so many hams are interested in extending its range. One thing you can do is attach an external antenna to the HT to give it greater radio coverage. This will increase your simplex range and allow you to hit more distant repeaters. Another thing to consider is establishing a VHF/UHF home base station, which provides more output power to increase coverage.

With regard to HT’s and radios for the ham shack, from my own perspective: My first radio was a Baofeng BF-F8HP ($60 at that time). The Baofeng radios are frowned upon by many of the older hams and do have a slight learning curve to program them. However, I have found mine to be adequate for my needs and have no complaints. My thoughts when purchasing the Baofeng were: 1) it was relatively inexpensive and therefore if I found that amateur radio was not for me I could donate it to someone new to the hobby and wouldn’t be out that much money and 2) if I enjoyed being a ham I could use it as a back-up or again donate it to a new ham. If you decide to purchase a Baofeng, Dan Rund in the repeater section of this website offers a wealth of information about Baofeng radios.

I shortly added a Yaesu FT-1500M that can be used either as a VHF/UHF base station to add range or mobile use.

I “jumped the gun” thereafter and bought my first HF radio, an older Kenwood TS-830S, that had a price I couldn’t pass up. Having a limited background in older radio/TV repair I also felt I could fix most of whatever broke. But, I did find, after being a ham for awhile, that it lacked a few features and a band I would have liked to have (I would probably have bought it anyway).

With that said, I offer the following advice. Your choice of radio(s) will greatly depend on what area(s) you chose to concentrate. That area should be your first consideration. Like all modern appliances; there are good ones, bad ones, and some horrible ones, amateur radio seems to have more that its share of each. 1st – Before purchasing any equipment take careful stock of your electronic capabilities. If opening up the inside of electronic equipment and doing circuit tracing seems like a daunting task, used equipment is probably not for you (although it can be very satisfying to bring older equipment back to life). 2nd – Many will find that purchasing the latest $3000 HF unit with all the latest “bells and whistles” is above their means and they are relegated to purchasing used equipment. Again, like the purchase of any major appliance, do your research. Before any purchase, seek help from other hams or the Club to which you belong. Find out if there are any major concerns regarding your choice and who they consider reputable suppliers. Get on-line and see what others are using. Look to u-tube, groups.io, and the internet for forums about any equipment you’re considering purchasing. 3) And last, don’t forget those resources you gathered before your purchase. They can be of great help in getting through the glitches and quirks of your new equipment.

Single Sideband on VHF

The majority of VHF operating is using FM, but there is another world out there in the weak-signal operating modes. This is called “weak signal” since you are often pulling signals out of the noise to make a contact. Signal Sideband (SSB) is the preferred voice mode when signals are weak since FM performs poorly when the signal level drops. You’ll find quite a bit of CW communication used since it is even better than SSB when the signals are weak.

To use SSB, you need an all-mode transceiver that operates on VHF. You will also need to get a suitable antenna, one that is horizontally polarized and possibly a yagi antenna with gain.

The 6m band is known as The Magic Band because it can suddenly come alive with signals bouncing off sporadic-e clouds in the ionosphere. On most days, 6 meters acts like any other VHF band with mostly local propagation. But when the sporadic-e hits (very common in the summer months), you can talk across North America. When the normal sunspot cycle is strong, you can also get F2 propagation, which allows contacts to be made into Europe, South America and Asia.

Space Contacts

Another use of the 2m and 70 cm bands is to contact outer space. The International Space Station (ISS) has a ham radio station on board and most of the astronauts have their amateur radio license. The primary use of this station is for contacts with schools as part of the NASA education outreach mission. However, the astronauts sometimes decide to make contacts on their own time. It really depends on the interests of the astronaut and a few of them have really gotten into making random ham radio contacts. Very often there is a packet radio station transmitting from the ISS such that you can “digipeat” through the station to contact other hams on earth. It is a fun exercise to see if you can successfully track the ISS and then hear the packet station transmitting. The ISS is in low earth orbit (LEO), so it is usually overhead for only 10 minutes or so, depending on the pass.

Another type of space operation is using OSCAR (Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio) satellites, which are basically repeaters in the sky. These satellites are also in LEO so you repeat through them to contact other hams while you both have the satellite within range. Some of these satellites use FM, so you can work through them using just a dual band (2m/70cm) HT and a small yagi antenna. It does take a bit of study and practice to track the satellites, figure out the right frequency, point the antenna and adjust for doppler shift. But that is what makes it a fun learning experience and radio challenge. See the AMSAT web site for more information, and check out this Ham Radio School article: Amateur Satellite Contacts.

Summits On The Air

The Summits on the Air (SOTA) program is a great combination of hiking and portable ham radio operating. The basic idea of SOTA is to operate from a designated list of summits or to work other radio operators when they activate the summits. The designated summits are assigned scoring points based on elevation with scoring systems for both activators (radio operators on a summit) and chasers (radio operators working someone on a summit).

A basic VHF SOTA station is a handheld FM transceiver with a ½-wave telescoping antenna. The standard rubber duck on a handheld transceiver (HT) is generally a poor radiator so using a ½-wave antenna is a huge improvement. Just stuff the HT and antenna in a backpack along with the usual hiking essentials and head for the summit.

Packet Radio and APRS

Interested in digital communications via amateur radio. This is a great way to blend computer technology and radio communications. There are many ways to do this but packet radio is one of the most common on the VHF/UHF bands. Simply put, packet radio uses relatively slow speed modem tones (1200 or 9600 baud) fed into an FM transceiver using a Terminal Node Controller (TNC). The transmissions are in “packet form” using the AX.25 protocol, which is handled by the TNC. Think of it as “SMS text messaging before there was text messaging.”

One of the most common usages of AX.25 packet is the Automatic Packet Reporting System (APRS). APRS is quite versatile but the most common use is position reporting, with a robust set of internet-based mapping tools to plot the position of a particular ham radio stations.

Work the High Frequency Bands

A Technician license does give you some useful operating privileges on the High Frequency (HF) bands. In particular, Techs have voice privileges on 10 meters (28.3 to 28.5 MHz). When the sunspots are active, 10m is an awesome worldwide DX band. You literally can talk around the world. To do this, you’ll need a transceiver capable of SSB on the 10m band and a suitable antenna. The antenna does not have to be exotic — a simple dipole or 1/4-wave vertical can do well.

A list of amateur radio modes

Modes of communication (not exhaustive but covers the majority)

Amateurs use a variety of voice, text, image, and data communications modes over radio. Generally new modes can be tested in the amateur radio service, although national regulations may require disclosure of a new mode to permit radio licensing authorities to monitor the transmissions. Encryption, for example, is not generally permitted in the Amateur Radio service except for the special purpose of satellite vehicle control uplinks. Below is a partial list of the modes of communication used, where the mode includes both modulation types and operating protocols.

CW (Morse code)

Morse code is called the original digital mode. Radio telegraphy (RTTY), designed for machine-to-machine communication is the direct on/off keying of a continuous wave carrier by Morse code symbols, often called amplitude-shift keying or ASKS. It may be considered to be an amplitude modulated mode of communications, and is rightfully considered the first digital data mode. Although more than 140 year’s old, bandwidth-efficient Morse code was originally developed by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail in the 1840s. It uses techniques that were not more fully understood until much later under the modern terms of source coding or data compression.

Alfred Vail intuitively understood efficient code design: The bandwidth-efficiency of Morse code arises because its encodings are variable length, and Vail assigned the shortest encodings to the most-used symbols, and the longest encodings to the least-used symbols. It was not until one hundred years later that Shannon’s modern information theory (1948) described Vail’s coding technique for Morse code, giving it a firm footing in a mathematically based theory. Shannon’s information theory resulted in similarly efficient data encoding technologies which use bandwidth like Morse code, such as the modern Huffman, Arithmetic, and Lempel-Ziv codes.

Although commercial telegraphy ended in the late 20th century, Morse code remains in use by amateur radio operators. Operators may either key the code manually, using a telegraph key and decode by ear, or they may use computers to send and receive the code.

Analog voice

Decades after the advent of digital amplitude-shift keying (ASK) of radio carriers by Morse symbols, radio technology evolved several methods of analog modulating radio carriers such as: amplitude, frequency and phase modulation by analog waveforms. The first such analog modulating waveforms applied to radio carriers were human voice signals picked up by microphone sensors and applied to the carrier waveforms. The resulting analog voice modes are known today as:

- Amplitude modulation (AM)

- Double-sideband suppressed carrier (DSB-SC)

- Independent sideband (ISB)

- Single sideband (SSB)

- Compatible sideband transmission, also called amplitude modulation equivalent (AME)

- Frequency modulation (FM)

- Phase modulation (PM)

Digital voice

Digital voice modes encode speech into a data stream before transmitting it.

- APCO P25 – Found in repurposed public safety equipment from multiple vendors. Uses IMBE or AMBE CODEC over FSK.

- D-STAR – Open specification with proprietary vocoder system available from Icom, Kenwood, and FlexRadio Systems. Uses AMBE over GMSK with VoIP capabilities.

- DMR – Found in both commercial and public safety equipment from multiple vendors. Uses AMBE codec over a FSK modulation variant with TDMA.

- NXDN: Used primarily in commercial 2-way (particularly railroads). Equipment is available from multiple manufacturers. NXDN uses FDMA with bandwidths of 6.25 kHz common.

- System Fusion – Open specification with proprietary vocoder system available from Yaesu. Uses AMBE CODEC with C4FM modulation.

- FreeDV – Open Source Amateur Digital Voice. Uses LPCNet Quantiser CODEC with differential or coherent PSK.

- M17 – Another open source] digital voice mode based on Codec 2. Uses 4FSK. Utilizes punctured convolutional coding and quadratic permutation polynomials for error control and bit stream re-ordering.

Image

Image modes consist of sending either video or still images.

- Amateur television, also known as Fast Scan television (ATV)

- Slow-scan television (SSTV)

- Facsimile

Text and data

Most amateur digital modes are transmitted by inserting audio into the microphone input of a radio and using an analog scheme, such as amplitude modulation (AM), frequency modulation (FM), or single-sideband modulation (SSB).

- Amateur teleprinting over radio (AMTOR)

- D-STAR (Digital Data) a high speed (128 kbit/s), data-only mode.

- Hellschreiber, also referred to as either Feld-Hell, or Hell a facsimile-based teleprinter

- Discrete multi-tone modulation modes such as Multi Tone 63 (MT63)

- Multiple frequency-shift keying (MFSK) modes such as

- FSK441, JT6M, JT65, and FT8

- Olivia MFSK

- JS8

- Packet radio (AX25)

- Amateur Packet Radio Network (AMPRNet)

- Automatic Packet Reporting System (APRS)

- PACTOR (AMTOR + packet radio)

- Phase-shift keying:

- 31-baud binary phase shift keying: PSK31

- 31-baud quadrature phase shift keying: QPSK31

- 63-baud binary phase shift keying: PSK63

- 63-baud quadrature phase shift keying: QPSK63

- Frequency Shift Keying:

- Radioteletype (RTTY) Frequency-shift keying

Other modes

- Spread spectrum, which may be analog or digital in nature, is the spreading of a signal over a wide bandwidth.

- High-speed multimedia radio, networking using 802.11 protocols.

Activities sometimes called ‘modes’

Certain procedural activities in amateur radio are also commonly referred to as ‘modes’, even though no one specific modulation scheme is used.

- AllStarLink (ASL) connects amateurs and repeaters via the internet using the Asterisk (PBX) IAX VOIP Protocol.

- Automatic link establishment (ALE) is a method of automatically finding a sustainable communications channel on HF.

- Automatically Controlled Digital Stations (ACDS)

- Earth-Moon-Earth (EME) uses the Moon to communicate over long distances.

- Echolink connects amateurs and amateur stations via the internet.

- Internet Radio Linking Project (IRLP) connects repeaters via the internet.

- Satellite (OSCAR – Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio)

- Low transmitter power (QRP)

- Prosigns for Morse code

In short, there are many things that you, as a Technician, can do. It just depends on how technical you want to get.

.